SELF HELP 7

How To Publish A Book

This newsletter is my process of writing a self-help book, tentatively titled How To Make Money: Financial Advice For Poets. To see previous letters on topics such as collaboration, micromarketing, happiness, and passive income, click here. I promise they’re all equally valid. The last letter I sent out contained everything you needed to know to make a movie.

When I was an undergraduate at Illinois a local comic publisher saw me read at an open mic and said, “I’m going to publish your book!” And he did. He misspelled my name, and I had to split the publishing cost, and it wasn’t a particularly good book and probably shouldn’t have been published, but try telling someone in their early 20s that their book shouldn’t be published.

I sent my next two books, A Life Without Consequences and What It Means To Love You, to a new publisher in San Francisco. It was a blind submission. I didn’t have any connections, and I hadn’t studied writing, or the thing that most people study when they’re studying writing, which is how to get published (not really, but also kind of).

Mac/Adam Cage bought both books for $18,000 each and a laptop. Because my name was misspelled on my first book I was able to pretend that A Life Without Consequences was my first novel, so that was good.

A month or two after I sold those books, but before they were released, I was awarded a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University. I was the only person in the program who didn’t have a graduate degree in creative writing. Actually, it was all a surprise to me. I had forgotten applying for the fellowship and I hadn’t actually thought I would ever be a writer or make a living at it. Until then I presumed I would get into advertising at some point. Most of the time I wish I had. I think I would have been really good at advertising.

But writing was this thing I did with my spare time and I’ve never found anything better to do. When I’m flowing and the writing is going well that’s as much happiness as I ever access. And it’s worth remembering as a writer, where is your joy in your work? Stay connected to that. Be an artist if you can.

Anyway, at Stanford I learned all the stuff the other fellows had learned in the programs they attended. It was as if they had all gone to school on my behalf. And I should say here, with only one exception, I really really liked all the people I met at Stanford, students and faculty.

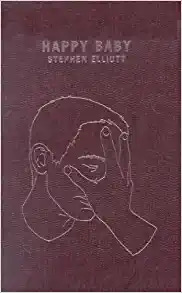

We met once or twice a week to workshop each other’s prose and I just hoovered the information. Some of them were clearly tired of being in workshops but I was learning stuff. And I wrote my first good book, Happy Baby.

Happy Baby was mostly a reaction to the workshop format. Because we were expected to comment on each others manuscripts, and maybe because when people didn’t know what to say they would ask, “Why?” Why was a character doing something? What was their motivation? And I realized I didn’t want to explain why my characters were doing anything.

I decided that I wasn’t going to tell the reader why my character was doing whatever they were doing. There would be no back story, no narration, no explanation. Everything was present tense written in scene, completely minimalist. The only thing that mattered was if it was plausible.

Honestly, I don’t even know my own motivations most of the time. It was my last novel, a kind of literary fundamentalism. I’d never write like that again.

So here are the lessons, which is always the point of this newsletter:

First, criticism can be just as good for finding out what you don’t want to do.

Get an agent, or don’t. The publishing world has changed beyond recognition but I didn’t have an agent for my first 4 books. And I published Happy Baby, my first good book, with MacAdam/Cage, for no advance and only 50% of foreign rights. They didn’t really care about the book, and I felt like I owed them a book because they’d published my other two. I don’t know, maybe it was the right thing. But I left a lot of money on the table. Because I was impatient. Because I didn’t know how to do things the right way.

And here is the weirdest lesson I learned from my experience as a Stegner Fellow, and publishing without an agent. I came to believe that good work would rise on its own merit. Happy Baby was released with no marketing whatsoever. It wasn’t even available for order at Borders, which is a bookstore that used to exist. But it made a bunch of best of the year lists, and I was nominated for a Young Lion’s Award from the New York Public Library and got a California book award. So I got this idea that it didn’t matter if you didn’t have an agent, if you didn’t get a big advance, if you didn’t do an MFA, and if you published with a small publisher.

I learned that if you focus on doing good work the work would find a way.

Which is absolute garbage obviously. I would spend the next 15 years learning otherwise. Never let someone tell you that connections don’t matter. Or the playing field is level. Or that life is fair. Or that things are how they are supposed to be or that it all works out in the end or that we live in a meritocracy. None of that is true.

BUT… you do kind of have to believe in meritocracy anyway (or meritocrazy, as I might start calling it). It’s like free will, or the American dollar. You believe in it because there is no other way to function, not because it’s true. You have to focus on the work as if it’s the only thing that matters. As if who your publisher was and whether you had an agent and how much money you got paid were not relevant to the success of the work.

Life is full of little fictions like this. My personal favorite is that it’s never too late. It’s always too late to start something yesterday. We have to believe though. There is still a reward for doing good work. There’s the process and we can focus on that as if it were prayer, or meditation. And it’s wonderful to feel that you wrote a couple of good books, especially if the weather is nice.

I never made much money as a writer. People who came from money always got bigger advances than me, and I think it’s because they know their worth. Though it’s a little more complicated, I’m sure.

Still, the best advice is always to be born wealthy and connected.

Anyway, the point I was getting at…

Oh yeah! How to publish a book! My first editor (on my second first book) had a great saying. He said, “The number one reason nobody is going to publish your book is because you haven’t written it yet.”

The best moment in the publishing process is after you’ve sold your book but before it comes out. It’s just like sex that way.

Never let a publishing question become a writing question. For example, if you’re concerned about writing about your family because of how they will react, that’s a publishing question. You can write whatever you want and decide if you want to publish it later. Don’t let publishing questions slow you down.

Get words on the page. Writing is editing. Writing is inefficient. Anything that gets words on the page is good, even when the writing itself is not good

Sell your book to whoever is offering you the most money.

Only self-publish your book if you’re in your early 20s and not famous, because it’s probably not that good anyway. And by the time you’re 30 you can pretend that it never happened. This might not apply to poetry, but it’s definitely true of novels.

I hope this was helpful. I’m going to do some more letters on How To Write soon, particularly on how to write from personal experience and how to ruin perfectly good relationships for no particular reason. If you have a topic idea feel free to send it my way.

Xoxo

p.s. I’m open to do a call or give personal advice on any of the topics covered in these self help letters for paid subscribers. I’m going to try to come up with other reasons to be a paid subscriber as well, but I don’t know if I’ll put any content behind a paywall. I guess I might at some point…

You can also send me a venmo (my Venmo page, I just realized, is unintentionally hilarious).

p.s. 2 Which reminds me, Nick Flynn owes me $10 for a bet we had about Trump pardoning the Capitol rioters. Apparently poets don’t Venmo.